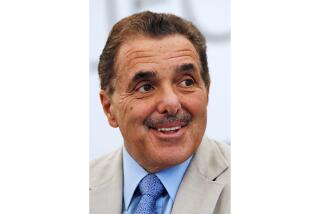

Good Reviews for Textbook Company : Publishing: Since taking over in 1989, David McCune has led Newbury Park-based Sage Publications through a recession to its most profitable year.

- Share via

In the 1970s, when David McCune worked for a Swedish tabloid, one story he covered involved a politician who was caught in a sex ring that involved bicycles and booze.

Two decades later, as president of Sage Publications Inc., McCune is turning out books on considerably tamer topics such as “Heuristic Research: Design, Methodology and Application,” and “Describing Talk: A Taxonomy of Verbal Response Modes.”

Since he took over the Newbury Park-based company in September, 1989, McCune has steered Sage through a recession to its most profitable year in 1991, as profits rose 12% from the year before to $865,000. Sales in 1991 were $13.9 million, a 6% increase over 1990.

Sage publishes scholarly books and journals geared primarily toward professors and upper-level college and graduate students in the social sciences. There is money to be made in its corner of the publishing market.

Sage’s profit margin for 1991 was 6%, a figure that exceeds Houghton Mifflin Co.’s 1991 profit margin of 5%, in what was considered a good year for the big-name textbook company.

McCune joined Sage early in 1988 because the company, started by his stepmother and father more than 25 years ago, was suffering growing pains. In 1986, the company lost $186,000--its first loss ever--and in 1987, his father, George McCune, reluctantly emerged from retirement to help turn the company around. Indeed, in 1987, Sage turned a $556,000 profit on sales of $7.6 million.

However, his parents were getting older and, like most companies, planning for the next generation of managers was a problem. When David McCune arrived, the textbook company, he said, “was as big as it ever was going to get being run by the founders.”

McCune, now 38, first stepped in as managing editor in charge of production and has modernized the company.

Essentially, McCune gave the company some professional management structure, which he said it sorely lacked. For instance, in the mid-’80s, either Sara Miller McCune, his stepmother, or his father had final approval of each jacket cover and marketing brochure, McCune said. Moreover, some book orders sat around in the company’s warehouse for weeks, and the production department delayed books for months at a time, he said.

McCune changed all that. Now, purchase orders remain in the company’s warehouse no longer than 48 hours. A move to desktop publishing has dramatically reduced per-page production costs. Before desktop publishing, Sage employed a laborious method of typesetting, which required the production staff to spend hours bent over a light table and was “like something out of Dickens,” McCune said.

The changes have kept Sage’s revenues growing. The company has more than doubled its revenue since 1986, and it has remained profitable the past five years.

In an effort to keep an entrepreneurial spirit alive while Sage expands, McCune brought in outside talent to launch two subsidiaries: Corwin Press Inc., which, unlike Sage, publishes books and journals geared toward educators of kindergarten through high school students. More recently founded Pine Forge Press Inc. publishes undergraduate-level social science texts.

Since September, 1989, McCune has run the company as president. As publisher and chairman, Sara McCune now scouts for new business ventures and acts as a liaison to the company’s London subsidiary and a Sage affiliate in New Delhi. George McCune died in May, 1990.

Despite its relative obscurity, in sales, Sage rivals the larger nonprofit university presses such as University of California Press and University of Chicago Press, which generate upward of $10 million per year in sales, according to Karla Golden, business manager for the University of California Press.

Sage has a good reputation in the social science scholarly community. “Sage is very reputable and a very good publisher of social science books. Their journals are in most libraries,” said David Cohen, marketing manager of the University of Texas Press.

“Each year, we’re ordering more from Sage,” said Barbara Lynch, textbook buyer for the UCLA campus bookstore.

Sage sells 40% of its books to college bookstores; about one-third is sold directly to individuals, according to McCune. The remainder of sales are divided between libraries, businesses and government.

In an odd way, the recession may have paved the way to Sage’s higher profits last year. Because of harder economic times, McCune delayed publication of about 30 books, saving as much as $280,000 in printing costs. In addition, McCune cut about $350,000 from the promotion budget by mailing fewer brochures, and he refused to promote books the company didn’t believe would deliver a profit.

“We were rather ruthless about that. It’s not nice for the authors of those books, I suppose, but that’s what we did,” McCune said. He said Sage makes 80% of its profit from about 20% of its books.

And all of Sage’s about 75 journals, which include such titles as “Rationality and Society” and “American Politics Quarterly,” turn a profit within five years or are dropped.

Sage was not the only publisher to fare well last year. Sales of university press books were up 8% to $265 million in 1991, compared with 5% growth in the publishing industry overall, according to estimates from the Assn. of American Publishers.

Terry Heagney, spokesman for Houghton Mifflin Co., said university presses and small scholarly presses may be insulated from the problems faced by large college textbook publishers that compete for a greater share of the market. “When you have a very, very small market share and you do a few things that improve your position, relative to the existing market, you can show growth,” he said.

Unlike Houghton Mifflin, Sage does not publish an introduction to economics or psychology textbooks, which can produce large sales but also must contend with an extremely competitive market. Instead, Sage focuses on publishing specialized research, which the company markets through direct-mail brochures to very selective mailing lists, such as social workers interested in child abuse prevention.

Sara McCune founded Sage in 1965 at the age of 25, soon after leaving as sales manager at Pergamon Press in Oxford, England. She moved Sage from New York to California four months before her marriage to George McCune in 1966. McCune, who had been a director of sales during part of his 13 years with Macmillan, a New York-based publishing house, later joined Sage.

Sage is not David McCune’s first foray into the world of business. Before coming to Sage, McCune owned a software development company in New York called the Proteus Group Inc., which designed software that allowed subscribers to retrieve articles and other information electronically. Prior to that, he was an editor of an electronic news delivery project at Time Inc.

McCune, who in his younger, more footloose days spent seven years living in Sweden, said he never expected to end up running a company.

But he seems to have put his heart into his new role. “I don’t want to stay at Sage and have it be a $15-million company. There are not enough zeros on that number.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.