Photos: Unsettled: Exide

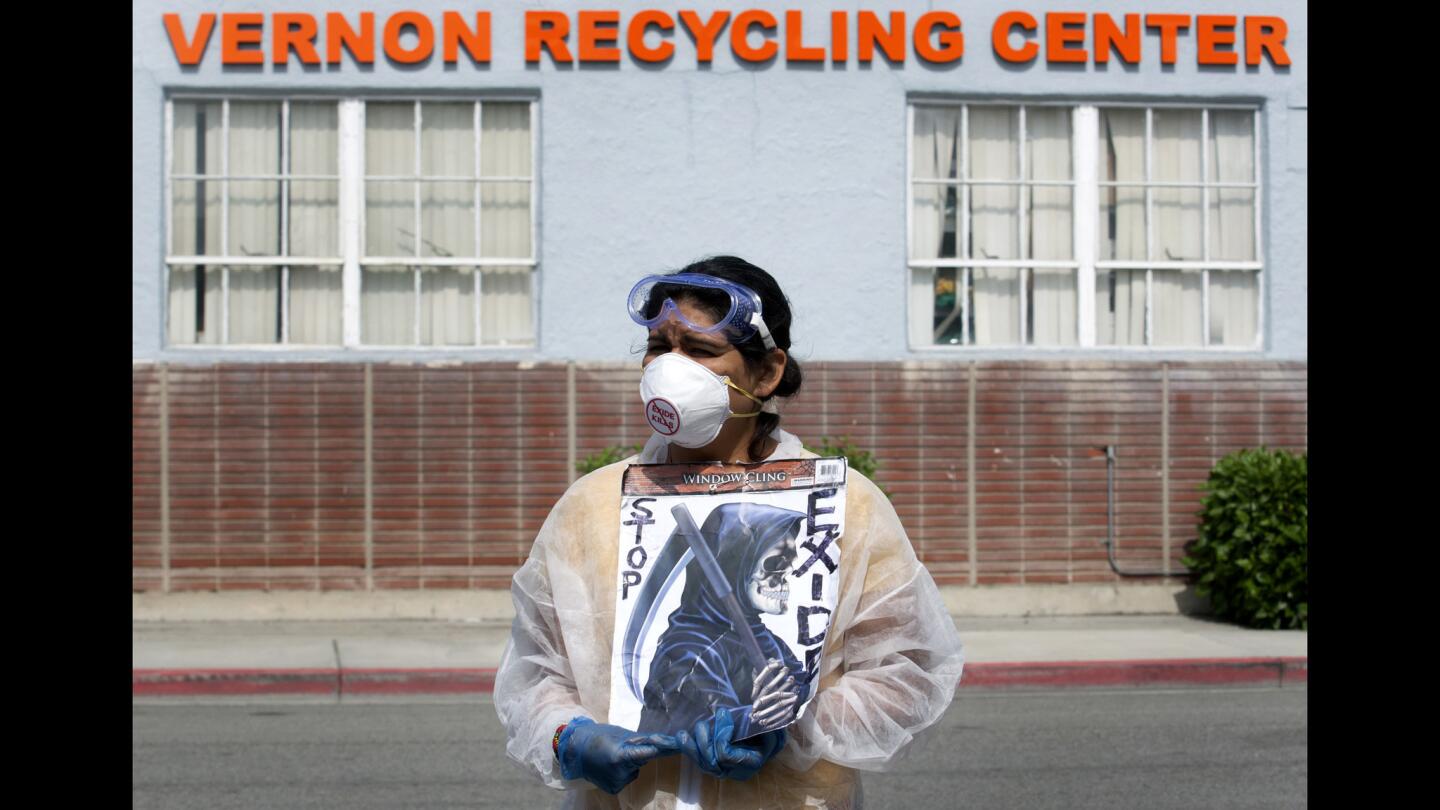

A protester wears a face mask during a rally outside the Exide battery recyling plant in Vernon in October 2013. Protesters demanded the plant’s immediate shutdown.

(Christina House / For The Times)Exide Technologies’ battery recycling plant in Vernon ran afoul of environmental regulations for decades.

Juan Rosales, 17, right, and Rossmery Zayas, 16, both of South Gate, march with activists, community members and leaders to the Exide plant in Vernon in an October 2013 protest.

(Christina House / For the Times)

Jonathan Sanabria, 25, of Huntington Park, bottom, participates in a rally outside the plant in October of 2013.

(Christina House / For the Times)

Testing in some yards of Boyle Heights homes near the Exide plant showed elevated levels of lead. Above, Boyle Heights resident Crystal Garcia, 26, with her 4-year-old daughter, Melonie, and her 3-year-old son, Jesse.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

Community members in March 2014 again sought the Exide plant’s shutdown in March 2014, during a community meeting at Resurrection Catholic Church in Boyle Heights on the results of lead testing.

(Lawrence K. Ho / Los Angeles Times)

Alicia Rivera, left, Maya Herrera and Carmen Garcia, chant as they join Communities for a Better Environment and the California Environmental Justice Alliance at a rally calling for statewide action on the Exide plant’s lead and arsenic emissions.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times)

Sofia Sanchez attends an April 2014 news conference outside the Exide recycling plant in Vernon. At the conference, the California Latino Environmental Adovcacy Network asked the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to investigate the plant.

(Cheryl A. Guerrero / Los Angeles Times)

Children in August 2014 watch while work to remove soil from the front and rear yards begins at the first of several homes in the Boyle Heights area where high levels of lead were found due to contamination by the Exide battery plant.

(Mark Boster / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

Hazardous waste hauled from the Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon leaked from trailers onto public highways in what a state environmental inspector in 2013 called an “ongoing problem” that “needs to be addressed immediately,” public records show.

(Michael Robinson Chavez / Los Angeles Times)

Boyle Heights resident Veta Gashgai, 40, holding her son during a November 2014 news conference. Community members demanded stronger protections for residents and legal action against the Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

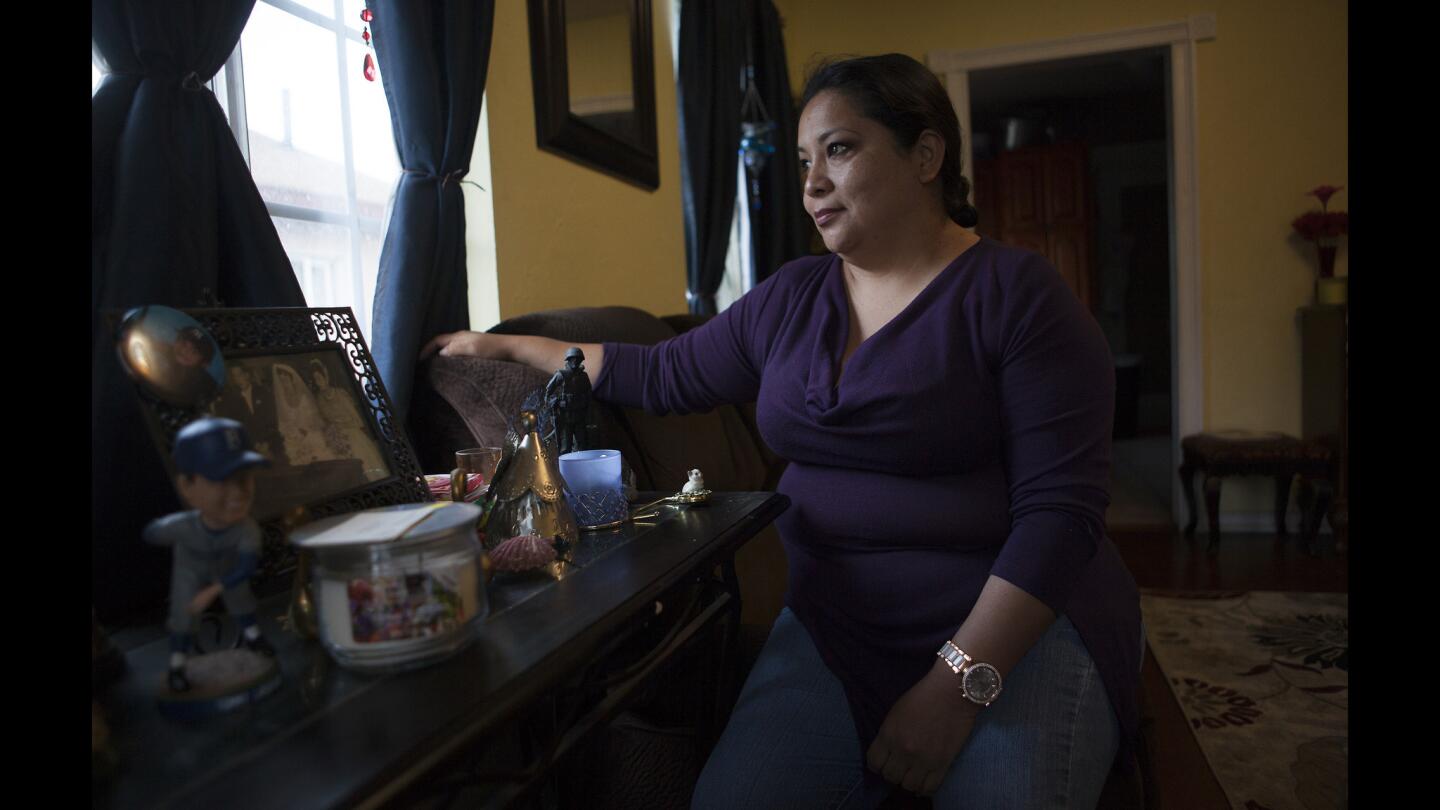

Terry Gonzalez-Cano, a Boyle Heights resident, believes emissions from the Exide battery recycling plant in Vernon sickened her and other family members.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Terry Gonzalez-Cano hugs her son, Edward. Gonzalez-Cano believes emissions from Exide Technologies battery recycling plant in Vernon have sickened her and other family members.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

Theplant operated in the industrial city of Vernon since 1922, spewing toxic air pollution over decades. Georgia-based Exide took over in 2000. Strict new regulations forced the plant to go idle in 2014. In March 2015, the company agreed to close the plant permanently.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

Msgr. John Moretta of the Resurrection Church in Boyle Heights on March 12, 2015, describes how Exide pollution affected residents after an agreement that would lead to the plant’s permanent closure was announced.

(Bob Chamberlin / Los Angeles Times)

Workers in Boyle Heights remove soil that may have been contaminated by lead. The neighborhood sits about three miles from the now-shuttered Exide plant.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)

Workers remove possibly contaminated topsoil from the yards of homes in Boyle Heights.

(Irfan Khan / Los Angeles Times)Advertisement

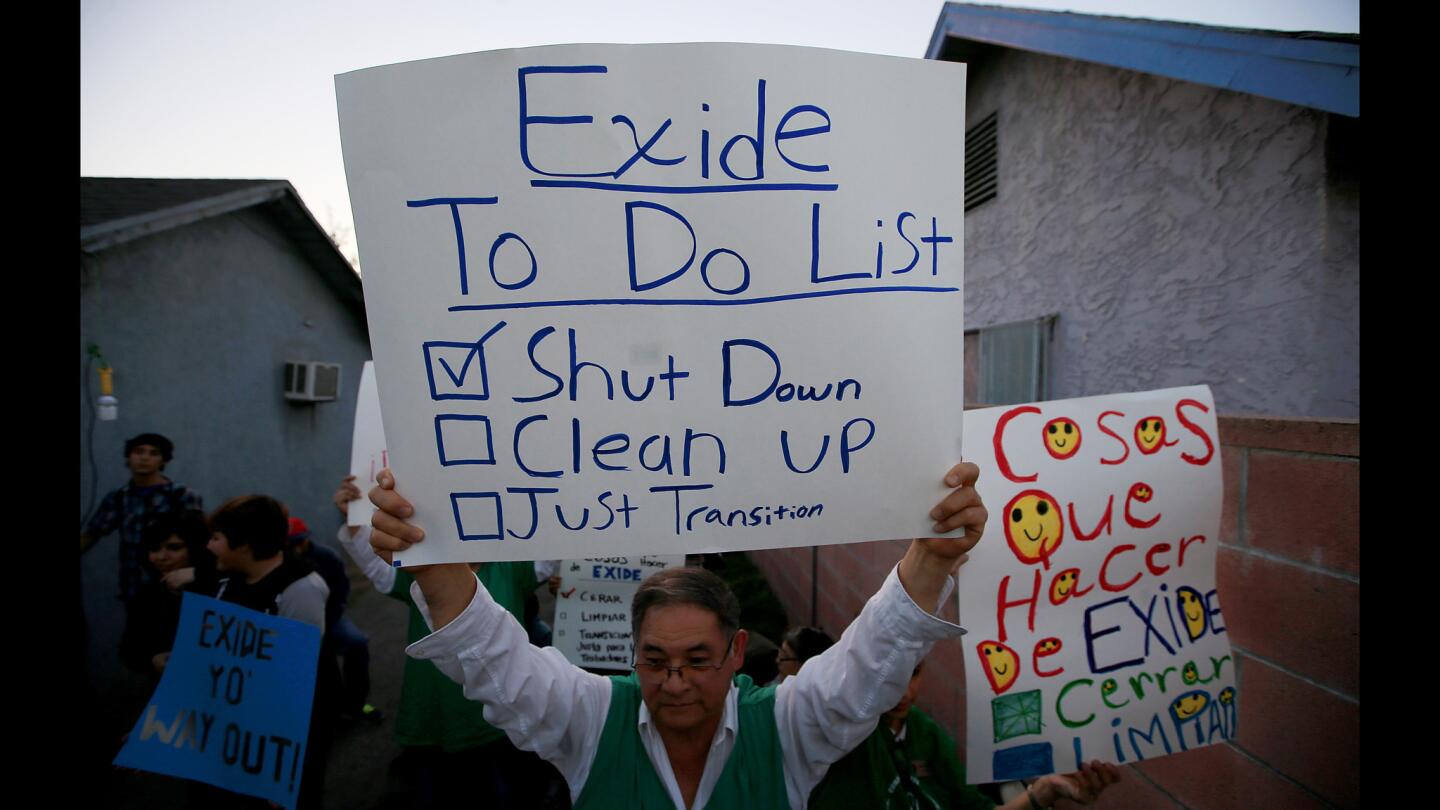

Community members and activists gather to celebrate the closure of the Exide battery recycling plant on March 12, 2015. But many still wonder why it took state regulators so long to act.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Community members celebrate the plant’s permanent closure. Under a deal with the U.S. officials, Exide and its employees avoided prosecution for years of crimes, including illegal storage, disposal and shipment of hazardous waste, while agreeing to pay $50 million to demolish and clean the plant and surrounding communities.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

Boyle Heights resident Patrick Valentine waters his newly installed lawn after the Department of Toxic Substances Control in August dug up at least a foot of the soil and replaced the grass in his front yard after detecting lead contamination.

(Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times)