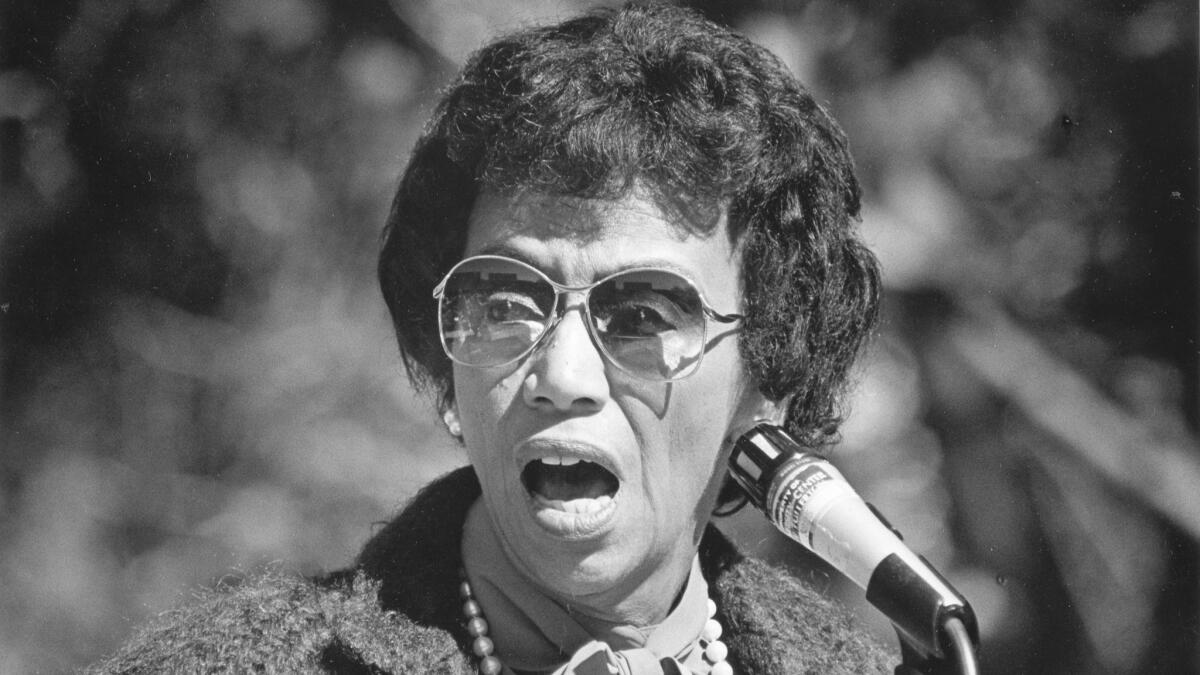

Jewel Plummer Cobb, who broke racial barriers as Cal State Fullerton president, dies at 92

- Share via

Jewel Plummer Cobb, the president of

Cobb had been living in Maplewood, N.J., and suffered from Alzheimer’s disease.

When Cobb arrived at the Orange County campus in 1981, she found a school bursting at the seams and lacking diversity — no campus housing for students, no women’s studies programs, few minority faculty members and officials who seemingly paid little attention to community outreach.

Cobb set about making changes, partially through the sheer force of her no-nonsense management style and constant 16-hour workdays, colleagues said.

“Jewel was an absolute dynamo. Her life was dedicated to helping the disadvantaged, long before that became a popular cry,” said Jack Bedell, professor emeritus of sociology and former chairman of the university’s Academic Senate. “Right away, she set an example for the rest of us that the university’s first responsibility is to students.”

Cobb, the granddaughter of a freed slave, told Bedell that her background compelled her to focus on the needs of those often ignored. She grew up in Chicago, raised by a doctor and a teacher. Though she came from a middle-class upbringing, segregation meant she had to attend underfunded public schools designated for African Americans.

While she was a student at the

A biologist by training, she never let go of her desire for lifelong learning, friends said.

“Once, my son opened up his sixth-grade science book and there she was, one of six people featured as leaders in her field,” Bedell recalled. “She always had high standards; she was classy in every way.”

By the time she retired from Cal State Fullerton in 1990, her legacy would include rapid enrollment growth, the opening of new communications and engineering schools, the launch of a satellite campus in southern Orange County and a public-private venture to build a Marriott hotel on campus. She was dubbed “The Queen of Concrete” by some.

Cobb was also credited with recruiting more women and minorities, both as students and professors. She established the school’s first endowed professorships and launched partnerships with universities abroad, forming overseas student and faculty exchanges, along with getting state funding for a dormitory that now bears her name.

Cobb’s own research focused on skin cancer and zeroed in on the ability of melanin to protect skin from damage. She spent years documenting how hormones, ultraviolet light and chemotherapeutic drugs could cause changes in cell division. Her published works include 36 research-related journal articles, plus others dealing with the advancement of women in scientific fields.

“She often told me that she faced more struggles as a woman than as a minority,” Bedell said.

What Cobb left behind is an appreciation for affirmative action — tied to excellence, said Barbara Stone, former political science professor and a member of the search committee that recommended Cobb for the president’s post.

In 1990, when asked how she would like to be remembered, Cobb told Diane Ross, then-president of the Association for Women in Science: “I think I’d like to be remembered as a black woman scientist who cared very much about what happens to young folks, particularly women going into science.”

She is survived by a son, Roy Jonathan Cobb; a daughter-in-law, Suzzanne Douglas Cobb and a granddaughter, Jordan.

ALSO

'Exorcist' author William Peter Blatty dies at 89

Dave Dutton, the landmark L.A. bookstore owner, dies at 79

Lynne Westmore Bloom, the artist who surprised Malibu with the 'Pink Lady', dies at 81

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.